What is WCAG? A Plain-Language Guide

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are the international standard for making digital content accessible to people with disabilities. Created by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), WCAG helps developers, designers, and content creators build websites and apps that work for everyone.

If you've ever wondered whether your website is accessible, WCAG provides the answer—and the roadmap to get there.

Why WCAG matters

More than 1 billion people worldwide live with some form of disability. When digital content isn't accessible, it creates barriers that prevent people from reading website content, watching videos, filling out forms, shopping online, accessing essential services, and participating fully in digital society.

Beyond the moral imperative, WCAG compliance is increasingly a legal requirement. Many countries have laws requiring digital accessibility, including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the United States, the European Accessibility Act (EAA) in the EU, and similar legislation worldwide. Organizations that fail to meet accessibility standards face legal risks, reputational damage, and the loss of customers.

But accessibility isn't just about compliance—it's about good design. When you design for accessibility, you create better experiences for everyone. Captions help people watching videos in noisy environments. Clear navigation benefits users who are distracted or in a hurry. High-contrast text is easier for everyone to read.

The four POUR principles

At the heart of WCAG are four fundamental principles, represented by the acronym POUR.

Perceivable

Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive. This means:

- Providing text alternatives for images

- Offering captions and transcripts for audio and video content

- Ensuring content can be presented in different ways without losing meaning

- Making it easier for users to see and hear content

Government example: A city council meeting video with slides showing budget data. People who are blind or have low vision need audio descriptions that explain what's shown in the charts and graphs, not just what council members say about them.

Operable

User interface components and navigation must be operable by all users. This includes:

- Making all functionality available from a keyboard (not just a mouse)

- Giving users enough time to read and use content

- Avoiding content that causes seizures (like rapidly flashing elements)

- Helping users navigate and find content easily

Government example: A dropdown menu on a county website should be navigable using Tab and Enter keys, not only clickable with a mouse. People with motor disabilities might rely entirely on keyboard navigation.

Understandable

Information and operation of the user interface must be understandable. This means:

- Making text readable and understandable

- Making content appear and operate in predictable ways

- Helping users avoid and correct mistakes

Government example: Error messages on a permit application should clearly explain what went wrong and how to fix it. Instead of "Error 402," say "Please enter a valid email address in the format name@example.com."

Robust

Content must be robust enough to be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. This includes:

- Using clean, standards-compliant code

- Ensuring compatibility with current and future assistive technologies

- Following semantic HTML practices

Government example: Using proper HTML heading tags (h1, h2, h3) instead of just making text bigger helps screen readers understand content structure. This lets people with visual disabilities navigate through a long zoning ordinance efficiently.

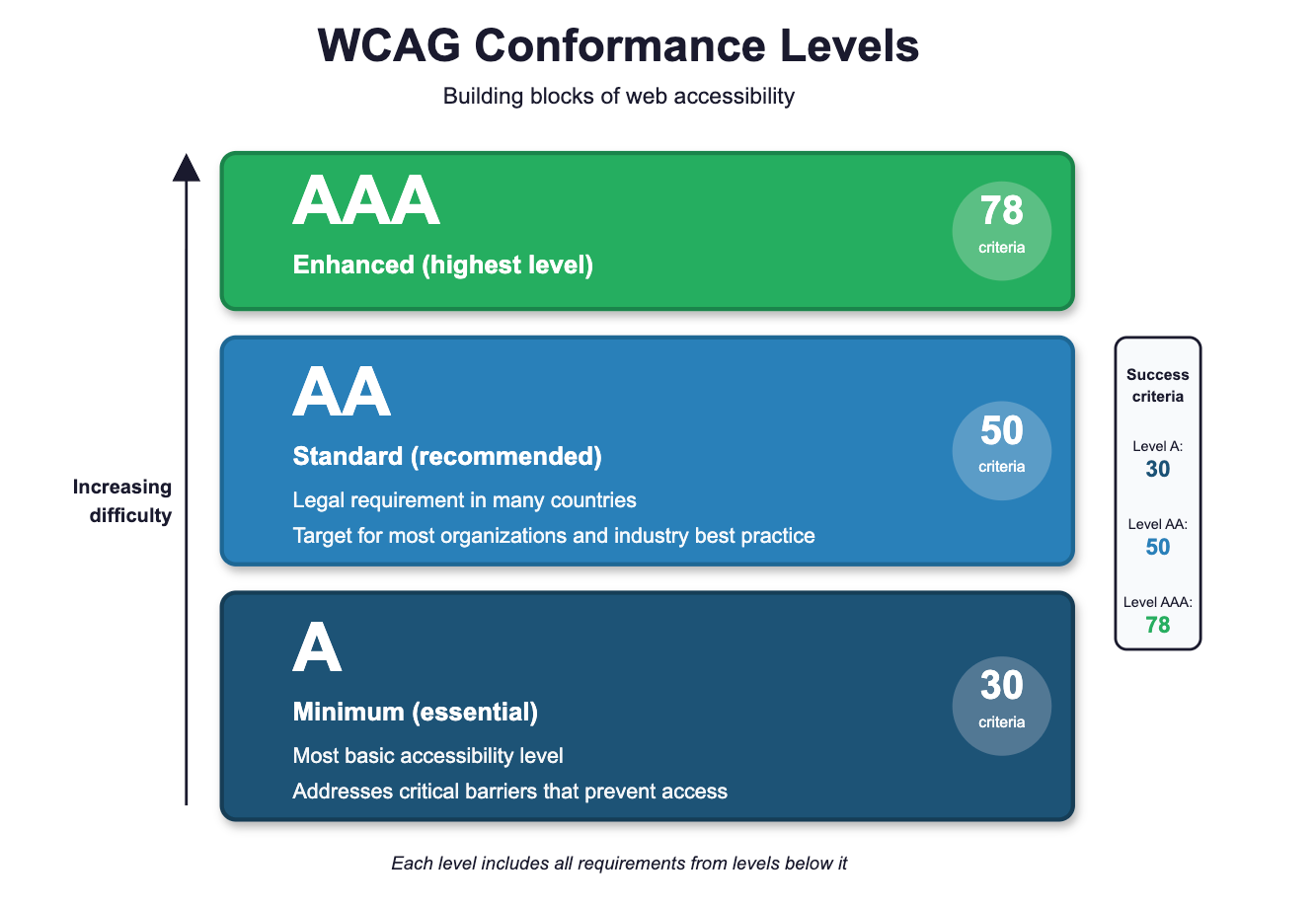

WCAG conformance levels

WCAG organizes its success criteria into three levels, each building on the previous one:

Level A (Minimum)

This is the most basic level of accessibility. If you don't meet Level A, some users will find it impossible to access your content. Level A addresses the most critical barriers.

Example criteria: Providing text alternatives for images, ensuring keyboard accessibility, providing captions for pre-recorded video.

Level AA (Standard)

This is the level most organizations aim for and what many laws require. Level AA addresses the major barriers for most users with disabilities and is considered the standard for accessibility compliance.

Example criteria: Ensuring sufficient color contrast between text and backgrounds (at least 4.5:1 for normal text), providing captions for live audio content, ensuring all functionality is available from a keyboard.

Level AAA (Enhanced)

This is the highest level of accessibility. While it's not realistic for entire websites to meet Level AAA, specific pages or sections might achieve this level. Level AAA provides the most comprehensive accessibility.

Example criteria: Achieving higher color contrast ratios (7:1), providing sign language interpretation for videos, ensuring minimal background audio in recordings.

Most organizations should target Level AA as their baseline goal. Level AAA is aspirational for most content, though certain audiences or contexts might require it.

WCAG versions: what you need to know

WCAG has evolved over time, with each version building on previous work:

WCAG 2.0 (2008): The first major version, establishing the POUR principles and three conformance levels. Still referenced in some laws and standards.

WCAG 2.1 (2018): Added 17 new success criteria focused on mobile accessibility, low vision, and cognitive disabilities. This version addresses modern web usage patterns and is the current legal standard in many jurisdictions.

WCAG 2.2 (2023): The latest version, adding 9 new success criteria to address gaps in mobile accessibility, users with cognitive disabilities, and low vision users. Includes improvements for focus indicators, dragging movements, and authentication.

WCAG 3.0 (In development): Expected to introduce a new conformance model and scoring system, though it's still in working draft status.

For most organizations today, WCAG 2.1 Level AA is the target standard, though WCAG 2.2 represents best practices and forward-looking compliance.

Common WCAG requirements in practice

Here are some practical examples of what WCAG compliance looks like:

Color contrast: Text must have sufficient contrast against its background. Normal text needs at least 4.5:1 contrast ratio; large text needs 3:1.

Keyboard navigation: Users must be able to access all interactive elements using only a keyboard, and the focus indicator must be clearly visible.

Alt text: All meaningful images need descriptive alternative text. Decorative images should have empty alt attributes (alt="").

Form labels: Every form input needs a clear label that stays visible, not just placeholder text that disappears.

Headings: Content should use proper heading structure (h1, h2, h3) to create a logical outline.

Link text: Links should make sense out of context. Avoid "click here" and instead use descriptive text like "Download the annual report."

Video captions: All pre-recorded video content needs synchronized captions. Live video needs real-time captions.

Getting started with WCAG

Implementing WCAG doesn't have to be overwhelming. Here's how to begin:

- Assess your current state: Use automated testing tools like WAVE, Axe, or Lighthouse to identify obvious issues. But remember that automated tools only catch about 30% of accessibility issues.

- Prioritize high-impact fixes: Start with issues that affect the most users, like missing alt text, poor color contrast, and keyboard accessibility problems.

- Build accessibility into your process: Train your team, include accessibility in design reviews, and test with real users who have disabilities.

- Test with assistive technology: Use screen readers (like NVDA or JAWS), keyboard-only navigation, and voice control to experience your site as users with disabilities would.

- Document your accessibility statement: Be transparent about your accessibility efforts, provide contact information for accessibility issues, and commit to ongoing improvement.

Summary: Key takeaways

- WCAG is the international standard for digital accessibility, created by the W3C

- The four POUR principles (Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, Robust) form the foundation of accessible design

- Level AA is the standard target for most organizations and often required by law

- WCAG 2.1 is currently the most widely adopted version, with WCAG 2.2 representing current best practices

- Accessibility benefits everyone, not just people with disabilities

- Implementation is an ongoing process, not a one-time project

What's next

Start with WCAG 2.1 Level AA as your baseline, use the POUR principles to guide your decisions, and remember that accessibility benefits everyone. By following WCAG, you're not just meeting a standard—you're building a more inclusive web.

Need help implementing WCAG? Consider consulting with accessibility specialists, using automated testing tools as a starting point, and most importantly, involving people with disabilities in your testing process. Real user feedback is invaluable for creating truly accessible experiences.